.jpg)

As a writer, poet and musician, Roxy Gordon published over 250 pieces of writing in addition to many newspaper columns and book reviews. He had two books published: Some Things I Did and Breeds as well as dozens of poems and short stories appearing in anthologies of American lndian literature. He recorded five albums and self-published six books of poetry and short stories. He wrote articles for The Village Voice, Rolling Stone, Country Music Magazine, and No Depression. He also co-wrote two plays with Choctaw author LeAnne Howe. Starting in 1980 and until his passing, Roxy performed hundreds of readings and concerts all over Texas, New Mexico, Montana, Oklahoma, and a few other states and performed fundraisers for the American Indian Movement. In the 1990s he attended dozens of college and school workshops and performances on writing and Native American Indian studies.

.jpg)

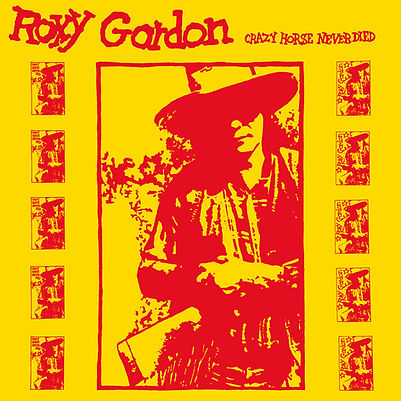

Crazy Horse Never Died New Re-Issue/Release

From Paradise of Bachelors Records

The ten songs on Crazy Horse Never Died, his first officially released and distributed album, were recorded in Dallas in 1988. “Songs” is perhaps an imprecise taxonomy for what Roxy captured on this and his other albums, all of which remain out of print or were released in instantly obscure limited editions of homebrew cassettes and CD-R’s. (Paradise of Bachelors plans to reissue remastered, expanded editions of his catalog; Crazy Horse is the first.)

Crazy Horse Never Died comprises songs that span the personal and political arcs of his writing practice and the poles of his native and white ancestries. His introduction to the almost-title track in the strikingly illustrated poetry chapbook supplement to the album (included in the LP edition of the reissue and also available for purchase separately) draws explicit parallels between the oppression and displacement of Palestinians by Zionists and the similar treatment of Native Americans by Europeans, justifying the historical necessity of resistance to racist imperialism through terrorism.

.jpg)

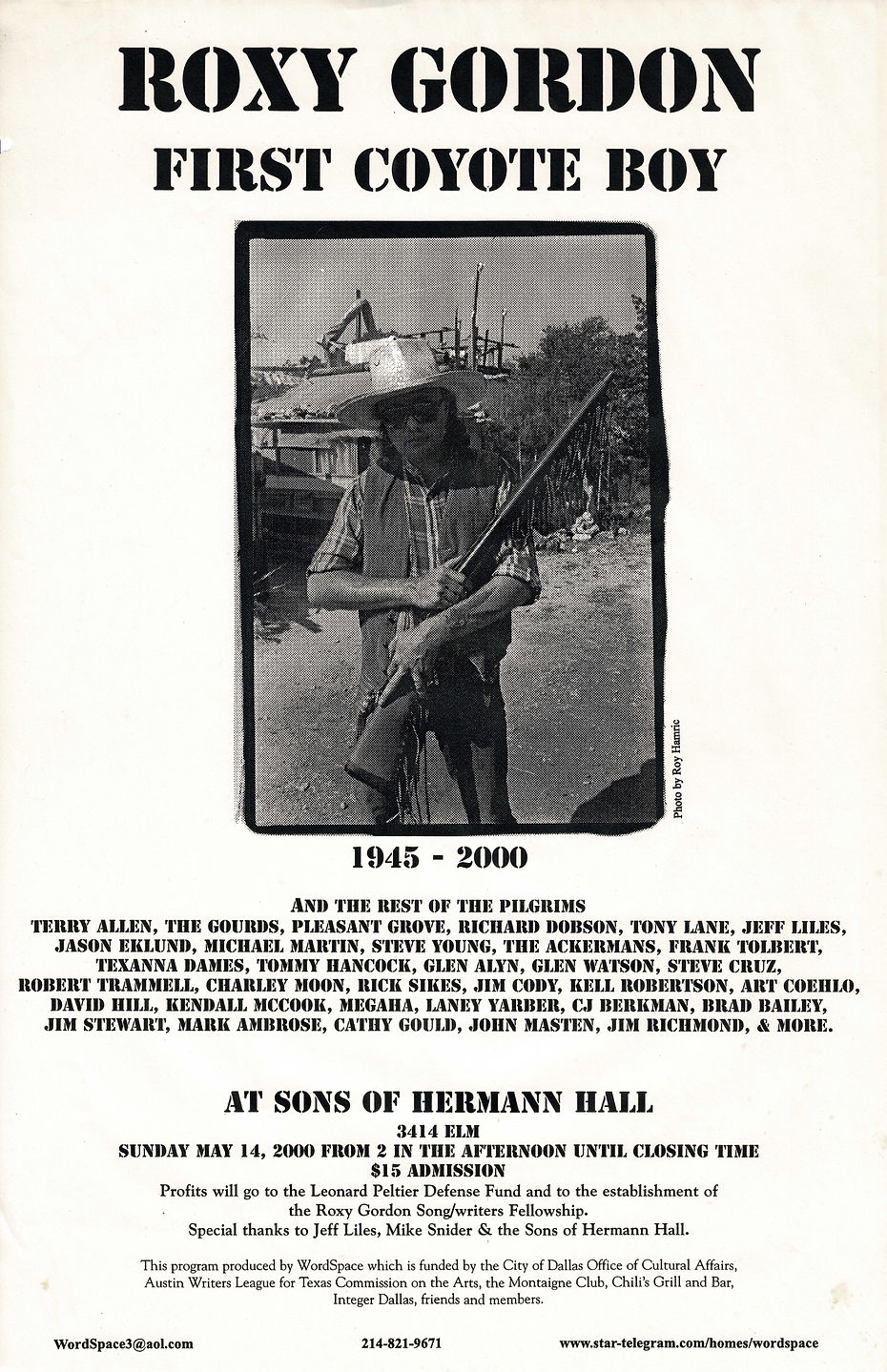

Rare Breed and Dove's Feet: First Coyote Boy Resurrects Crazy Horse in Dallas

by Brendan Greaves

Everything is very, very strange. At the time of writing, a debate still rages about the legality and morality of separating the children of undocumented immigrants and asylum seekers from their parents while in detention at facilities near the U.S.–Mexico border, and, appallingly, whether to extend due process to “illegal” immigrants to the United States at all. Through 2016 and 2017, the widespread (and ultimately unsuccessful) protests at Standing Rock and beyond to halt the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline, which Sioux and Meskwaki tribal leaders asserted would threaten both sacred sites and local water quality, galvanized and united indigenous peoples alike across North America and beyond. I can only assume that these persistent issues—how our government fails to respect the civil rights of the country’s natives and newcomers alike—will continue to hang thick in the air like sickly, crooked smoke. These are old stories, recursive but still raw.

In 1988, the Texan and American Indian poet, multimedia artist, activist, and musician Roxy Gordon released a song called “An Open Letter to Illegal Aliens” on his debut solo album Crazy Horse Never Died (technically his second full-length recording, following Unfinished Business [1985], but the first to see proper release and distribution). The LP was one of a clutch released by the tiny independent UK-based label Sunstorm, which was named for a 1985 album also called Sunstorm, by singer-songwriter (and sometime Sunstorm artist) John Stewart, who in a weird twist of pop history, was both a member of the anodyne folk revival group the Kingston Trio and also wrote the Monkees’ 1967 hit “Daydream Believer.” Peter O’Brien, fellow poet and songwriter as well as editor and publisher of the legendary, small circulation British music magazine Omaha Rainbow, for which Gordon wrote many beguilingly digressive essays and album reviews—mostly about nominally country and western artists circulating in so-called “outlaw” circles—from the late 1970s through the late 1980s, was instrumental in founding Sunstorm, and funding, producing, and releasing his friend’s recordings of his extraordinary, distinctive songs.

“Songs” is perhaps an imprecise taxonomy for what Roxy recorded on this album and scattered others, all of which remain out of print or were released in instantly obscure limited editions of homebrew cassettes and CD-R’s. (Paradise of Bachelors plans to reissue remastered, expanded editions of his catalog; Crazy Horse is the first.) Gordon was above all a storyteller, known primarily as a writer of inimitable style and unvarnished candor, whose wide-ranging work encompassed poetry, short fiction, essays, memoirs, journalism, and criticism. He only occasionally attempted to sing, and his musical recordings are primarily corollaries of, and vehicles for, his texts. His sharp West Texan drawl, tinged by formative years of reservation living and unmistakable once you hear it—nasally, high, lonesome, flat, and cold-blooded as a bare rusty blade—instead patiently unfurls in skewed sheets of anecdotal verse and discursive narrative rants. Like some Lone Star avatar of the Fall’s Mark E. Smith or Jamaican DJ U-Roy, only less traditionally rhythmically inclined, you get the sense he might say anything next, or might keep talking forever from some febrile place outside himself, carried along by the inexorable current of his own peculiar cadence, its dry heat. The shallow modulation of Gordon’s speaking voice suggests deep, expectant distances, monotonous drives toward the broad horizons and through the crazed, sun-harshed sepia landscapes of West Texas, where you can see the gray seams of storm clouds and rain columns miles away across the seemingly boundless flatlands but may never meet their wind or wet. (Relatively concise on record, during performances the pieces could go on for ten minutes or longer.) I find Roxy’s voice—the sometimes unlovely, piercing sound of it, its grim humor, and its bemusement about our shared culpability and onrushing mortality—arrestingly strange and singularly moving.

Gordon cultivated close friendships with fellow Texan songwriters such as Lubbockites Terry Allen, Butch Hancock, and Tommy X. Hancock, as well as Ray Wylie Hubbard, Billy Joe Shaver, and, most famously, Townes Van Zandt. (Gordon was precisely one year younger and died almost exactly three years to the day later than Townes; drinking buddies, partners in crime, and, sadly, mutual enablers, they called each other brother, and so they were.) For a while Roxy and his wife Judy published a country music magazine called Picking Up the Tempo, and for another while, they operated a small publishing company called Wowapi Press. He moved in diverse circles, Indian, white, and beyond. (Smaller Circles [1997] is the title of his most widely known album, produced by and featuring his friend, British musician Wes McGhee.) He did time managing a Dallas office for and touring with David Allan Coe.

Although Gordon’s music at times incorporated powwow style drumming, fiddling (in the great tradition of Choctaw fiddlers), or unaccompanied ballad singing, the majority of it hews to an idiosyncratic spoken word style, accompanied by atmospheric, sometimes synth-damaged country-rock that skirts ambient textures and postpunk deconstructions. His songs are essentially recitations over backing tracks of fingerpicked guitars, rubbery washtub bass, and buzzing, oscillating keyboards. On the stark yellow and red jacket of Crazy Horse, which he designed himself, Gordon describes these recordings as innately ambivalent in terms of form, content, and identity:

These are poems and/or songs about the American West, white and Indian. My life has been Indian and/or white. Maybe there’s not a lot of difference—maybe. I guess that’s mostly according to which white person or which Indian you’re talking about. That’s probably what this album’s about.

Here is the Indian and/or white life we’re talking about: Roxy Lee Gordon was born to Robnette L. (Bob) and Louise (Bomar) Gordon on March 7, 1945, in Ballinger, Texas, an only child of the American West (though, like Elvis Presley, he apparently had a twin brother who died at birth). He grew up in rural Coleman County, on the fringes of Talpa, about fifty-five miles, or an hour’s drive, due south of Abilene, in the heart of West Central Texas. His mother and grandfather were both musicians, and Roxy took up guitar as a teenager (later he played drums too) before moving to Austin to attend the University of Texas, where he edited the student literary magazine Riata. Gordon identified his ancestry as mixed Choctaw and Scottish—or half Choctaw, half Texan—and in the late 1960s, a few years after marrying Judy Nell Hoffman in 1964, the young couple moved into a one-room log cabin in Lodge Pole, Montana, on the Fort Belknap Indian Reservation, immersing themselves in the Assiniboine (Nakota) and Gros Ventre (A’aninin) communities there. Gordon assessed the rather radical decision with characteristic laconism: “Born Choctaw, not knowing much about the rest of Indian America, I wanted to find out. Finding out started then.” During their time in Lodge Pole the Gordons published Fort Belknap Notes, a weekly newsletter about reservation life.

After leaving Montana, they embraced an itinerant bohemian lifestyle, with spells in San Diego, where Roxy briefly studied at Cal Tech, met Jim Morrison of the Doors, and befriended novelist Richard Brautigan, poet Robert Creeley, and actor Rip Torn; outside Albuquerque, where they founded Picking Up the Tempo and Wowapi Press while Roxy pursued journalistic endeavors; and, for two decades, from 1976 to 1997, in Dallas, a block off Lower Greenville Avenue. It was there that Roxy founded a local chapter of the American Indian Movement (AIM) and made most of his recordings (including Crazy Horse, with accomplices Brad Bradley, who arranged and engineered, on keyboard and guitar and visual artist and chili chef Frank X. Tolbert2 on washtub bass). He read his poems and performed regularly in Dallas, Austin, San Antonio, throughout Texas, and further West, sharing stages with Bob Dylan, Leonard Cohen, Ernest Tubb, and Erykah Badu, among many others. In 1991, at a traditional Sundance ceremony at Fort Belknap, Gordon was officially adopted by his old friends John and Minerva Allen into the Assiniboine tribe, taking the aptly tricksy name First Coyote Boy (Tu Gah Juk Juk Ka Na Hok Sheena) and thereby tethering his identity to a third homeland in addition to Texas and the ancestral lands of the Choctaw (which lie within what we now call the South—originally modern-day Alabama, Florida, Mississippi, and Louisiana—but which predate that designation and all others in European tongues).

The Gordons’ cluttered East Dallas home, brimming with art, artifacts, and books, and trussed with animal hides and bones (locals called it “the bone house”), proved more permanent than others, attracting a ragged and dedicated scene of artists, activists, poets, singers, seekers, and misfits from all over Texas, the nation, American Indian nations, and Britain, where Roxy had a cult following thanks to the support of O’Brien and McGhee. He became increasingly active in the movement to free AIM activist Leonard Peltier, organizing several fundraising concerts. His final years were spent back at his family’s homeplace in Talpa, where he and Judy returned in 1997 in part to care for his ailing mother and elderly grandmother. Roxy received visitors in a rickety, hand-built studio/campsite/sculptural environment that he called the House-Up, overlooking the Gordon property.

After a long struggle with cirrhosis of the liver, First Coyote Boy died on February 7, 2000, a month shy of his fifty-fifth birthday, beloved by his many allies and admirers, but underrecognized by the literary and musical establishments and doomed by his unquenchable addiction to alcohol. Judy passed away on July 10, 2022, survived by her two children with Roxy, John Calvin (“J.C.”) Gordon, who has assumed the role of archivist of his father’s legacy, and Quanah Parker Gordon, his father’s sometime accompanist on fiddle and drum.

He left a lot of work, most of it uncollected. Over the course of his career Gordon published six books (including the excellent, and perfectly titled, 1971 memoir Some Things I Did, about his Vietnam War-era stint volunteering for the antipoverty VISTA program in Colorado, right before he and Judy decamped to Montana) and hundreds of shorter texts—essays, short stories, poems, plays, reviews, artist profiles, creative nonfiction, and news items—in outlets ranging from Rolling Stone and The Village Voice to the Coleman Chronicle and Democrat-Voice. He recorded six albums, including, in addition to the three already mentioned, two live recordings (Live at 500 Café, Dallas and Kerrville Live) and the posthumously released 2001 studio album (and accompanying chapbook) Townes Asked Did Hank Williams Ever Write Anything as Good as Nothing, once again with his chief musical collaborator Wes McGhee. Although his work covered a vast array of topics exploring strata personal, local, global, and cosmic alike, Gordon’s primary subject as a writer, musician, and visual artist was always American Indian culture, specifically the ways it collided and coexisted with European American culture in the South and West—and within the context of his own life and braided identity.

Crazy Horse Never Died comprises songs that span the personal and political arcs of his writing practice and the poles of his native and white ancestries. Sometimes abrupt tonal and metaphorical shifts, discontinuities, and lacunae bely his seemingly plainspoken verse by amplifying the essential ambiguities of his understated and unpretentious poetry. (“Mostly it’s the spaces between things where I feel comfortable,” Roxy once wrote.) His introduction to the title track in the strikingly illustrated poetry chapbook supplement to the album, originally published separately in 1989 but sharing the same title and reproduced in this volume, draws explicit parallels between the oppression and displacement of Palestinians by Zionists and the similar treatment of Native Americans by Europeans, justifying the historical necessity of resistance to racist imperialism through terrorism. On “Junked Cars” he describes his sometimes lonely youth in Talpa amid the desolate landscape and the human wreckage of discarded material culture:

I spent my mysterious childhood

hunting human sign

over miles and miles

of empty

Texas West.

I hunted rusted tin cups and

broken bottles where adobe houses

melted and where dryland farmers’

deserted shacks moaned low in

summers’ winds ...

Junked cars were beautiful to me then

because they offered proof

of living human flesh.

“The Hanging of Black Jack Ketchum” and “The Texas Indian” confront the complexities and contradictions of Texas history and Gordon’s own family history, which included several Texas Rangers, infamous hunters of Indians and Mexicans. The frenetic, synth-spraying “Living Life as a Moving Target” and the chilling, sinister-sounding “Flying into Ann Arbor (Holding)” confront the complexities and contradictions of mortality, the blind forces that threaten and ravage us, collectively and individually, externally and internally. “The Western Edge” begins in Hollywood, at “Chuck Berry’s girlfriend’s house” (listen to how he savors and then spits out those words), and then careens amiably right off the continent, over the Pacific Ocean ledge. Stabs of sly humor such as heard here punctuate the album with winks of recognition. Jokes elicit laughter, and blood rises to smiling faces, revealing bloodlines. (In 1999, paraphrasing his acquaintance R.A. Lafferty, the singularly weird and wonderful Oklahoman author of the fictionalized Choctaw historical saga Okla Hannali [1972], Gordon wrote that “when two strange Indians met in the old times, if they each burst into laughter, then they’d know they were both Choctaw.”)

“I Used to Know an Assiniboine Girl,” the devastating, brokenhearted centerpiece of the record, tells a tragic, elliptical tale of domestic violence and a young woman’s governmental punishment for defending herself, all refracted through the narrator’s deep regret and sorrow as a spectator to her brutalization. As he bluntly explains in the spoken introduction, regardless of extenuating circumstances, “Indian girls up in Montana don’t beat up white guys and not expect to spend time in the penitentiary.” (And so it remains today, with the systemic abuse, murder, disenfranchisement, and incarceration of native women.) His voice audibly aches as he confronts how his own desire and inaction have implicated himself in her predicament, tracing her strength back to their people’s resistance to the iterative, genocidal violence perpetrated against them.

But I had another woman and I never said a word.

I kept all I wanted to myself.

So she came to spit at me, came to call

my name with fire,

offered actually to fight me with her fists.

And, my God, I loved her then; I looked

behind her brown eyes,

I saw a nation that’s gone born again.

I saw lean and screaming riders race for buffalo.

I saw a hundred-thousand free and haughty men.

“An Open Letter to Illegal Aliens” is just over three minutes long. It is both a dirge and an antiracist protest song. Gordon’s vocal cadence recalls the incandescent pitch of a fire and brimstone sermon, and the song itself resembles a pre–WWII recording of a gospel sermon, a genre popular in the 1920s and 1930s, with stars such as J. M. Gates of Atlanta, Georgia. Gordon sounds like an irreverent beatnik Choctaw incarnation of Hank Williams’s gospel persona Luke the Drifter, but funnier, more profane, and more menacing. As a church organ synth swells and recedes in waves, Gordon enumerates a litany of diseases—namely, capitalism, communism, materialism and money, Christianity, and Judaism—the “baggage” imported by European immigrants to “these American continents,” which had been doing “pretty well” for some forty thousand years before their arrival. They all “kill and steal,” and each has its own victims. This acid retort to conservative white America’s hysteria about immigration is, in the end, a rather compassionate and tolerant transposition. It’s the ideological baggage that is not welcome on “these American continents,” not those foreign human beings who bear it, who in Gordon’s estimation might be just “as native American as Crazy Horse” (note the lower case “n”), even if they do not behave that way. Introducing the song in the Crazy Horse Never Died chapbook, Gordon writes breathlessly that:

The overwhelming hypocrisy of a nation descended mostly from gangs of illegal alien thieves, which closes down its borders to latecomers (who themselves are mostly descended from the race that got stolen from) is so obvious that I swear I don’t know how it can get away with it.

In his 1984 essay “Breeds,” from the fine collection of the same name, he concludes with a note of hope:

The voices of these continents are not stilled because, for a few centuries, this land is overrun by human beings who cannot hear. Over years of cultural and racial genocide, over centuries of lies and misdirection, That Which Is still calls . . . and the old American blood in us listens.

Roxy’s friend and fellow poet-turned-musician Leonard Cohen had kind words for Breeds, writing: “It is strong. The word goes out. Can a change come on dove’s feet?”

Crazy Horse Never Died begins and ends with a typically equivocal response. The narrow howl of a single distant wolf opens the record with a summoning, a lonesome convocation. The final sound we hear on the album is a chorus of wolves, a pack’s howls massed and keening in an eerily prayerful farewell.

The smoke has gone up. The talk is over with. Only howling remains. Bestir that old American blood and listen.

Chapel Hill, North Carolina

2018/2022

Writer/Poet/Musician/Artist/Indian Activist

Roxy Gordon was born in Ballinger, Texas and grew up in the small West Texas town of Talpa. He wrote about growing up

"I spent my mysterious childhood hunting human sign over miles and miles of empty Texas. I hunted rusted tin cups and broken bottles where adobe houses melted and where dryland farmers' deserted shacks moaned low in summer's wind. Junked cars were beautiful to me then, because they offered proof of living human flesh."

Roxy attended the University of Texas in Austin where he edited the official student literary magazine, Riata. "Stayed at UT way too many years then went to the Fort Belknap Reservation in northern Montana. Born Choctaw, not knowing much about the rest of Indian America, I wanted to find out. Finding out started then. Assiniboine and Gros Ventre. One room log cabin in Lodge Pole, Montana. My wife, Judy, and I edited, published and produced the weekly reservation newsletter, Ft. Belknap Notes." Later, in July, 1991, he was adopted into the John and Minerva Allen family of the Assiniboine Indian tribe at the Fort Belknap Reservation. Of his Assiniboine family, Roxy wrote "I had known John and Minerva and their kids for over 20 years. Judy and I first went to live at Fort Belknap in the spring of 1968. John was on the Tribal Council and had been Tribal Chairman. Minerva was an educator and poet."

He was adopted and named at a traditional Assiniboine Sundance. (The Sundance is a major - perhaps the most important - ceremony of plains Indian religion and culture.) He was named Tu Gah Juk Juk Ka Na Hok Sheena, meaning First Coyote Boy, First Boy because he was a bit older than Little John, John and Minerva's oldest birth son, and Coyote because he was from south of Montana and the Coyote is the animal of the South.

Some Things I Did

From Montana to California to Texas

In 1969, Roxy and Judy moved to Oakland, California. Roxy wrote of the move "Judy and I had left the Montana res for San Diego where I attended a summer course in writing. One of the teachers was the now long suicided Richard Brautigan, an original Haight-Ashbury hippie, a digger who furnished food for wannabe hippie kids during the Summer of Love, and at that point, probably the most popular and best selling poet and prose writer in college-kid America. We became friends. He said come to San Francisco, didn't mention flowers in the hair. We had some fed money left from the res, planned to go home to Coleman County, but I had read Post Magazine about San Francisco and the Haight, so we figured to take detour."

In 1970, Roxy returned to Texas for an extended visit home with intentions to return to California. But on returning to California, Roxy wrote "At the end of the Texas year, we headed, tentatively, toward San Francisco to resume our previous position – this time, probably even in a better role because I had just published a book. But at the KOA campground in Santa Fe one night, I had a good long, serious talk with myself about the nature of true Stardom and we took off for El Paso, instead, where we spent five months starving, unrecognized, sitting at A&W Drive-ins and driving the streets to look at pretty Chicano girls."

His first book: Some Things I Did, published by Bill Wittliff of Encino Press, Austin, Texas.

Book Review Excerpt by Steve Barthelme, The Texas Observer, March 17, 1972

There’s a touch of anarchism about a regional press issuing Roxy Gordon’s first book in the quiet blue matte finish of standard quality Texana. But the disparity between the quiet traditional beauty of the book object and the mean beauty of Roxy Gordon’s mind is somehow pleasant – it, like the book itself, forces conflict which reminds you that you’re alive. Some Things I Did doesn’t go out of its way to be easily assimilable, and that too is refreshing because so much of what is published today is very easy to assimilate, that is, understand, that also is, forget.

It is Roxy Gordon's gift, in Some Things I Did, to be self-conscious without being so terribly serious, to be narcissistic without being nauseating. Add to that, the very personal way he describes his experience, and the intelligent, unique quality of his description, and you may well have the reason that Some Things I Did is worth reading and The Strawberry Statement is not. In a time when everyone seems to have such a tight grip on the truth, it is refreshing, and rewarding, to read someone who does not, and who does not care, because it is only from such a person that anyone ever gets any good information, or any intelligent conversation.

.jpg)

Review: Some Things I Did

.jpg)

Roxy Gordon

By Robert Trammell (From Hot Flashes #2 - January 1986)

The first time I met Roxy was when he & I were doing a reading together at 500 Exposition about 5 years ago. That night he read a longish poem “I Dreamed I Saw Joe Hill Last Night, Alive As You Or Me,” a real angry, hostile bit of writing & I assumed that was who Roxy was. I was prepared not to like him. That was stupid of me. My own work is at times violent & it really puts me off when people think therefor I am. Maybe I am, maybe Roxy is too but we both exorcise those demons mostly thru our writing (but the gun is real). As it turned out Roxy and Judy are about the most generous people I’ve ever met. They are honest and direct.

I’ve come to respect them both. I’ve also become a fan of Roxy’s no nonsense writing style. I learn from him & his work (he also paints & draws), am provoked & inspired by him to write from the heart as he always does.

Starting young, in 1963 he won a Talpa-Centennial High School Letter Jacket for writing. He may be the only person to have ever been so honored in Texas.

At the U. of Texas he was editor of Riata, the school’s literary mag. Soon after graduation he wrote Some Things I Did (Encino Press, Austin, 1972), made some money & got some notoriety. The book had a lot to do with his living on the Ft. Belknap Indian Reservation in Northern Montana. Roxy is a Breed, part Choctaw. His work often reflects that heritage. In the ‘70s he published, edited & wrote for the small but influential monthly mag Picking Up The Tempo. Lots of his friends (Townes Van Zandt, Butch Hancock, Billy Joe Shaver, Richard Dobson, Jimmy Gilmore & the Lubbock-by-way-of-Fresno Terry Allen) still write songs. That makes sense cause, till now, this state has sure turned out better songwriters than poets. In 1984 Place of Herons Press published Breeds, his most important collection/book. In 1985 Judy Gordon started her Wowapi Press & published his most recent book Unfinished Business. He has had work in Greenfield Review, Omaha Rainbow, The Sun, Art Magic (which he published) & Earth Power Coming.

Roxy & Judy have been building a kinda Comanchero camp/house/enclosure near Talpa. They call it the HouseUp. They spend as much time as they can out there but still have to make a living in Dallas. They grew up together & both of their families still live there. Judy’s father runs an old-fashioned ranch & traps game. While we were visiting he trapped, skinned & gave me the pelt of a Ring Tail Cat. He can only get $3 for them. They are sent to Russia & made into mittens. Roxy nailed it to a board, cured it with formaldehyde. It’s on my hall wall next to the rattlesnake skin to remind me as Roxy & Judy always remind me that Dallas is just a stopping place on their way back home to Coleman County.

Wowapi Press and Picking Up The Tempo: A Country Western Journal

From Albuquerque, New Mexico to Dallas, Texas

Roxy and Judy moved to Albuquerque, New Mexico, and expanded their publishing company, Wowapi Press. They also edited and published a country western music magazine called Picking Up The Tempo. Picking Up The Tempo ran for nearly three years centering on the alternative Nashville country scene, with articles and interviews of Willie Nelson, Waylon Jennings, David Allan Coe, Kris Kristofferson, Billy Joe Shaver, Tommy Hancock, Freddy Fender, Dolly Parton, Doug Sahm, Kinky Friedman and many others as well as coverage of several of Willie Nelson's early 4th of July Picnics. Picking Up The Tempo focused on new and upcoming country artists, the origins of country music, the radio stations that supported and played country music, cowboys and rodeos, and the rich histories between country musicians and their roots in country music.

In 1977, Roxy and Judy left Albuquerque for Dallas, Texas, to work with David Allan Coe. Shortly thereafter, Roxy and Judy continued to publish books under Wowapi Press. Roxy illustrated a series of poems called Art Magic, which combined poems with graphic illustrations. He started writing extensively about Native Indians. In 1984, his book Breeds was published by Place of Heron Press, Austin, Texas.

In 1988, he released his first album Unfinished Business and in the following year of 1989, Crazy Horse Never Died on Sunstorm Records out of London, England, with an accompanying book of poetry. He performed and read on a weekly basis at places like the Prophet Bar, 500 Cafe, Poor David's Pub, Paperbacks Plus, Video Bar, Dallas Museum of Art, Theater Gallery, Caravan of Dreams, and the Kerrville Folk Festival.

Do You Know Willie Nelson?

Written by Roxy Gordon, Published in the Coleman Chronicle & Democrat-Voice

July 1995 - Kathleen Hudson had me to the college in Kerrville to do an Indian literary festival in May. She told me Willie Nelson was doing another 4th of July Picnic - this one in Luckenbach. She wanted me to come. Kathleen and I went to one in Austin, 1990. That was my fifth. I didn't make Dripping Springs, the first, which from all accounts was, not really Willie's folks, but some part of the Country Music Association with private investors.

I first met Mr. Nelson in about 1974. He did a private party in Albuquerque. He had shoulder length hair and no beard. Second time, he did a concert at the convention hall in Albuquerque. After the show, he was going to some singles bar to play. Judy didn't like the bar and advised him in no uncertain terms. Saint Willie did his usual grinning act with eyes not quite there. His drummer, Paul English, The Devil In The Sleeping Bag, settled her. Then there was the series of picnics. I was doing a magazine in New Mexico. I had a friend working at KOKE radio in Austin and she said she'd get backstage passes if I'd say I was going to do an edition on the second picnic, the one at the speedway at Bryan/College Station. We said okay and went. It was quite an event. I decided to do a one shot tabloid, decided to call it Picking Up The Tempo after the old Willie Nelson song. Sent it around to Austin and Nashville. Soon had people calling. Nobody had ever seen a country music publication like it. We published photos of topless young women in the audience. I ran into Faron Young and he told me in no uncertain terms he didn't approve. He was involved somehow in publishing Music City News in Nashville. He told me Waylon Jennings did not smell well.

Folks who called wanted to advertise. We kept doing issues. At the end, after four years, we'd only lost seventy dollars. But it got us into many a show for nothing and backstage passes, including Willie Nelson 4th of July deals. I'd always played music and, through the publication, met half the countryish musicians in North America. I stay in Dallas because I met David Allan Coe and he wanted me to help me run his office there.

Best backstage at a picnic was Bryan, probably 25 acres. Waylon rode with Sammi Smith in a Cadillac driving in circles. George Jones was afraid of the hippies and had his limo drop him directly at stage stairs. Tom T. Hall wouldn't even come. Doug Sham changed clothes down to his boxer shorts with red hearts printed. Sue Tewawina took photos of him but later discovered she had no film in the camera. A young woman roamed around wearing nothing but glued-on sequins. I decided Leon Russell was a true mutant. I got into a fight with one of the radio station guys and he forced himself into their trailer. Later at Denny's, I ran into Red Steagall and asked him why his band was called the Coleman County Cowboys. He said he'd never been to Coleman County; said his aunt's name was Coleman. Michael Martin Murphey sat with us. He was wearing a leather shorts outfit that Swiss yodelers affect.

Liberty Hill was bad. Mud six inches deep, backstage partitioned in plywood sections. I spent most time on David Allan Coe's bus. The car broke down on the way back to Valera, Texas.

Judy, a woman named Marsha (works for Warner Brothers now) and I drove David's new Cadillac to the Gonzales event. We parked just back of stage. Show went on all night. It was hot. We slept in the car, motor running, air-conditioner running. The place was full of bikers. The Outlaws were with David. The Angels were with Willie and Waylon. David packed a pistol.

Cotton Bowl in Dallas, people with fire hoses sprayed the audience.

Austin, I discovered backstage pass wasn't worth plastic printed. Took the thing off and had more nearly complete access. But then decided to go to the pickup for a drink. Passed a metal cage with a pretty young woman apprehended for goodness knows what. She cried and screamed at me to help her. Got back and security guy got me. I lied, told him I played guitar with Kimmie Rhodes. I'd known her for years and guessed she'd back my lie. Guard looked me over, head to foot, and said go on in. Billy Joe Shaver wondered around with his new wife who is no longer his wife. Some guy on stage wore a tee-shirt with my name on the back. Fireworks exploded. Kathleen and I escaped to the motel. She wanted to sleep, told me to shower picnic dirt. She did and commenced to crash. I decided to tell her the story of my life. She was sound asleep before I finished.

Luckenbach, Texas, day before yesterday. Judy and I slept in the back of the pickup front of Kathleen's house. When the morning comes and you got to get up, we take off for the event, following Kathleen who took two New Yorkers and one of her students. She had good enough sense to get there early. Had to park two miles away, get bussed in on school busses. Backstage passes were not to be found. Some guy at the gate knew who I was and said go on in. Went to the office and various folks there couldn't find passes. Finally, Judy and I went hunting and did. We sat by the old dance hall and watched the hoard pile in. Music started and we went backstage. David Allan Coe had taken chairs to the shade. I sat there seven hours, talked with David, met his newer wife, Jody, and oldest new kid, Tyler. People kept coming and saying hello. Naturally I didn't know almost any. David signed tee-shirts and guitars. He went to the bus to dress and I decided best idea I'd had in the world was to get out. That mass of humans was going to make a leaving traffic impossible. We split and spent early evening in Kathleen's side yard in silence.

Mr. Nelson is over 60 and may never have another picnic. I am 50 years old and told Judy somewhere around Menard I'd never do it again. But, then on the other hand, my mama says never say never because it just might change to will.

Wowapi Press

Wowapi Press publications since 1973.

Like Spirits of the Past Trying to Break Out and Walk to the West

By Minerva Allen

Animal Magnetism

By Jennifer Kidney

Rhythm Rebel

By Rick Sikes

Unfinished Business

By Roxy Gordon

Coyote Papers

By LeAnne Howe

Living Life as a Living Target

By Judy Gordon

Great Aunt Lessie Belle's Funeral

By Charley Moon

Minerva Allen's Indian Cook Book

By Minerva Allen

Readings 1987: Volume 1

From The Prophet Bar

Salty Songs

By Richard Dobson

Smaller Circles

By Roxy Gordon

Revolution in the Air

By Roxy Gordon

Townes Asked Did Hank Williams Ever Write Anything As Good As Nothing

By Roxy Gordon

West Texas Mid-Century

By Roxy Gordon

Wowapi: Anything Written In Any Form

By Judy Gordon

Tender Blue Flickers

By Karen X

Crazy Horse Never Died

By Roxy Gordon

Crazy Horse Notes

Written by Peter O'Brien

In November 1973 it was my admiration for singer/songwriter John Stewart that prompted me to publish Omaha Rainbow, a magazine named after a song John recorded on California Bloodlines, his first solo album after leaving The Kingston Trio.

Fast forward to 1977 and I was putting together the 15th issue which included two interviews with Townes Van Zandt. One of the shops here in London, England, that sold Omaha Rainbow was Compendium Books. It was there I had discovered Picking Up The Tempo. Included in one of the issues I purchased was an article, Townes Van Zandt might Be Arriving, written by its editor and publisher, Roxy Gordon.

I wrote asking if I might reprint that article in my magazine and he generously gave permission, adding that if I ever came to America I was welcome to stay with him.

The following year during the course of a phone interview John Stewart asked me, "When are you coming to America? "Is that an invitation?" I enquired. "Get your ass over here, O'Brien," he responded.

So it was in August 1978 I made my first trip to the USA, flying into Dallas/Fort Worth Airport to be met by Roxy and his wife Judy, who were to become two of my dearest friends, staying with them on numerous return trips in the long summer vacations from my day job as a high school physical education teacher.

It was during one of those visits Roxy began recording the songs that were to become the album, Crazy Horse Never Died. By this time I had also started a small record label, initially to put out a John Stewart album released to support one of his UK tours.

When Roxy sent me a cassette of his finished album I offered to release it on vinyl through my label, Sunstorm Records. Roxy happily accepted the offer and the LP was actually mastered from that cassette.

Just down the street from where Roxy lived was a fine music venue, Poor David's Pub. It was there I had seen Townes Van Zandt play and subsequently Roxy himself. It was also where Roxy and Judy got to see John Stewart a few times. John would invariably end the evening back at their house.

I'll end this as I began with John Stewart on whom Roxy had made quite an impression. Writing in his newsletter, The Finger, John said, "We jumped through the eye of the weather needle and hit Texas under bright skies and hot highways. There's a renegade poet-author named Roxy Gordon who lives in Dallas with his wife, Judy, and their two sons. Roxy has recently come into my life as my new, favourite writer. Someday, maybe Steinbeck will be my favourite writer again but, right now, it's Roxy Gordon. Roxy writes bone-lean, clear views of the world and the American Indian that makes me want to tear up what I've written and start again. Since every day I feel I'm starting again, I guess he just inspires me."

{Photograph of Peter O'Brien, Roy Hamric, Robert Trammell & Roxy Gordon}

.jpg)

The 1990s

From Dallas, Texas, to Home in Coleman County, Texas, and Lodge Pole, Montana

Living for over a decade one block off of the Dallas' Lower Greenville Avenue scene, Roxy continued writing, publishing and producing music. Becoming active in the American Indian Movement, he helped raise funds and awareness of Native Indian history, issues and social conditions. He released two more albums - Smaller Circles and Townes Asked Did Hank Williams Ever Write Anything As Good As Nothing.

Roxy continued to travel to Lodge Pole, Montana, to perform and educate on the Fort Belknap Reservation where he was adopted into the Assiniboine Tribe. Of these travels, he wrote "I expect I am double-blessed. I have a home and family in western Coleman County, Texas, and I have a home and family in northern Montana."

"Five years ago, over 15 years after I'd lived at Fort Belknap, I was up there and went to the Lodge Pole general store. This is an old-fashioned general store with all the goods behind the counter. You ask for what you want. I was waiting and a tall, old Indian came in. Schoolboard elections had been held that day. The old man waited beside me. 'Well,' he asked me, 'did you vote?' I said, 'No, I couldn't. I don't live here anymore.' He squinted at me. He asked me, 'Where do you live, now?' I said, 'Texas.' He looked a bit puzzled. 'When did you move?' he asked me."

In 1997, he uprooted from Dallas and moved back home to Coleman County where he and Judy lived on the same family country land that his grandparents owned. He continued to travel and perform and wrote extensively an ongoing column for the Coleman Chronicle & Democrat Voice. He wrote over 100 articles ranging from Texas history to Native American Indians to music and a lot of other stories about his life in between.

Roxy Gordon passed away on February 7, 2000, leaving a 35-year legacy of writings, poetry, music, and illustrations.